About two years ago, right about the time that I was improvising on the lazzo of la Fame dello Zanni ("The Starving Zanni"), a process that eventually resulted in Arlecchino Am Ravenous, I was also reading Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. As a consequence of this chance juxtaposition, the two have become bound up in my imagination.

The Merchant of Venice's reputation as an anti-Semitic text that relies on anti-Semitic stereotypes and has often been used to deliberately stir up anti-Semitic passions is well known. There are also numerous efforts to acknowledge this history and even find means to create a more complex reading that redeems the play in the eyes of our more modern, liberal sensibilities on ethnic and religious pluralism. After all, it's Shakespeare whom many argue to be the single greatest contributor to English language literature and drama. Some cite the following passage from Act III, Scene 1 as evidence that Shakespeare was actually philo-Semitic:

Some cite the following passage from Act III, Scene 1 as evidence that Shakespeare was actually philo-Semitic:

Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die?Often it is quoted in isolation, where it can serve as a powerful statement against antisemitism; that the Jew and the Christian are equally human. Yet the speech continues:

and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge! If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge! The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.The point of the passage was simply to state Shylock's motivation for vengeance after the heroes have lured him away from his house on business, robbed his home, and absconded with and converted his daughter and only heir (thus cutting off all connections with family and tribe) on top of all the indignities of bigotry that he and his community had suffered. Furthermore, Shylock is not treated as fully human until after he has been forcibly converted at the conclusion of the trial in Act IV. Though many commentators have noted that the Christian characters are portrayed as having many of the same vices as Shylock, he cannot receive mercy either before the court or in the divine sense, until he has left Judaism behind and become a Christian. While Shylock is a far more humanized portrayal of a Jewish character than his predecessors in English theatre (Marlowe's The Jew of Malta is so absurdly over-the-top that it was hard for me to be pained by Barabas' villainy) the anti-Semitic logic of the The Merchant of Venice remains: Only the Christian characters are blessed with the grace to be forgiven their vices; only they are fully human. The indignities they visit upon Shylock does not damn them, and in fact, they are oft times portrayed in a positive light because they are Christians. Indeed, the revenge speech indicts Shylock as engaging in hubris simply because he is not made fully human to Shakespeare's contemporary audiences until the end of Act IV when he submits to conversion under threat of death. (Yes, there is a complex set of ironies and contradictions contained within the play, but the anti-Jewish logic remains intact.)

What does this have to do with my portrayal of Arlecchino, the stock character of the commedia dell'arte?

In the full-length version of Arlecchino Am Ravenous (not the abridged ten minute version performed at the PuppetSlam this past weekend) Arlecchino visits both Heaven and Hell in his quest for food. I make no excuses, Arlecchino Am Ravenous is a work of comedic blasphemy and violence. Arlecchino is, unlike Dante Alighieri, an illiterate vulgarian incapable of grasping his journeys into Paradiso and Inferno except in terms of his hungers, lusts, frustrations, and the barely understood parables he's learned from his encounters with clergymen.

As I read The Merchant of Venice two connections struck me. The first was that the Gobbos, father and son, are of the same zanni archetype as Arlecchino. The second was that one epithet slung at Shylock with great frequency is "devil": Sometimes Shylock is said to be like a devil, and sometimes he is explicitly said to be the Devil (and young Launcelot Gobbo has a rather notable comic monologue in which he does just this.) It seemed quite reasonable to me to assume that once Arlecchino, being like the Gobbos, finally meets "Signor Diavolo Lucifero dell'Inferno" that he would say:

Who the diavolo you think you are?Once before, at a performance at the Gulu-Gulu Café in Salem, Massachusetts, I self-censored this brief passage. While at Blood for a Turnip, I engaged in no such act of censorship. (The entire journey to Heaven and Hell were left out when I performed at the PuppetSlam the following night, but those cuts were more because of time more than content.)

[Smiles in recognition, and bows.]

Oh! Buon Giorno! Signor Diavolo Lucifero dell’Inferno! Everyone say you look like Shylock, but no…

[To audience:]

…Shylock more handsome…

[Back to Lucifer. Mimes putting arm over Lucifer’s shoulder.]

…Signor Diavolo no look like Jew! More like goat.

Obviously, though some of Arlecchino's blasphemy may have shocked some in the audience, it was this brief passage that clearly made some in the audience uncomfortable (as well they should.) My own intent was to portray Arlecchino as being a product of the prejudices of his milieu: 16th century Italy while at the same time giving him the insight that despite what the Venetians of his era say: The Devil doesn't look Jewish, thus the Devil is not a Jew.

But is this what my audience gets from my performance of my play? Is this too much to ask the audience to ponder my meaning in the middle of a half-hour of physical comedy in a monologue conveyed largely in a made-up dialect?

Of course, there is also the question: can I be more clear with my intentions without breaking character?

I do not get a free pass on criticism because I am a Jewish theatre artist, nor do I get a free pass on this because I have taken other theatre artists to task when I have perceived anti-Semitic content (such as Peter Schumann's trivialization of the Holocaust, or Stephen Adly Guirgis' invocation of the deicide charge in Last Days of Judas Iscariot.) I don't get a free pass because Total War is about the historical legacy of antisemitism: While a full accounting would include these; I would still be accountable.

Likewise, to those who might find Arlecchino Am Ravenous' blasphemy disturbing, does my more serious treatment of religion in Total War absolve me? (Probably not.)

Or then again, am I just writing an essay in response to having told a joke in poor taste?

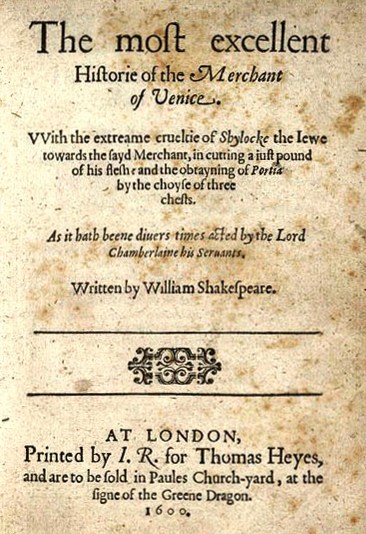

facsimile of the title page of the First Quarto edition of The Merchant of Venice courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

7 comments:

It's of course impossible to argue that The Merchant of Venice is not anti-Semitic. But it must also be admitted that it is ANTI-anti-Semitic. Feminists have the same problem with Shakespeare: he is seemingly sexist at many junctures, and yet he is probably the starting point of feminism on the stage.

And I can't agree that Shylock is "not fully human" until the horrifying finish of Act IV. Instead, I'd say he's the most human person in the play. He's certainly the most compelling character; he towers over his setting. And Shakespeare consistently subverts everything the Christians say, while affording Shylock a suprising level (for this playwright) of integrity. You're quite right that the play's mechanics are clearly anti-Semitic; and yet I have to say I think the overall effect of the play is anything but.

Maybe I am being unclear, Thom.

When I argue that Shylock is not fully human, I mean within the confines of the play's mechanics, that is to say, the structure and premises of the play as a historical artifact are not satisfied until he is forcibly converted-- and this is in part because Shakespeare is still working within the confines of the comedy genre as it was understood in his era: i.e. a happy ending where no one dies, and most of the characters are left with their situation bettered.

Now as 21st century folks whose conception of character is heavily informed by the way Shakespeare improved upon the established genre, you are absolutely correct. It's just that the "horrorifying finish", as you put it, of Act IV was a happy resolution for the 16th and 17th century English audience (though, Shakes might have made a few of his more sensitive audience members a bit queasy feeling about their pleasure.)

I just suspect that our ability to have a complex and nuanced reading of the play has as much to do with the era that we inhabit as with Shakes' genius-- but as for myself, even as a fan of the bard, I have to get past a lot of visceral reactions before I can even get to that nuance that you are talking about.

See, I'm still not writing about Boston College.

Yes, but isn't it strange that society only catches up with Shakespeare's subtexts over the course of centuries?

I of course understand your visceral reaction to this particular text. (My reaction to the anti-Semitic structure of the play is equally negative, but of course it's not personal.)

Still, I do wish that us postmoderns could at least keep Shylock in perspective. He's not, actually, the center of the play - sometimes it's been hardest of all for some of my Jewish friends to accept that. What is often ignored entirely about Merchant is its strange, incredibly profound meditation on the co-dependent nature of money and love.

Shakespeare might not have been able to catch up with Shakespeare. I suspect the reason there are so many levels of irony and subtext in his work may have less to do with a desire to communicate a particular message, but to keep himself (and his actors) amused with the work. He was the sort of genius who likes that sort of thing.

Part of the reason it's hard for Jewish audience members of The Merchant of Venice to disentangle the anti-Semitic material from the overall theme of the entanglement of love and money (both major themes of the Italian comedy) is because just such an entanglement is a central anti-Semitic trope.

But then again, I once read the play with a mostly gentile group and even they saw the pound-of-flesh arc as so central that they had trouble grasping the purpose of Act V.

Of course, it doesn't help that "Shylock" has long since become an ethnic slur (precisely why I'm asking for trouble when I invoke the name in my Arlecchino play.) It's not as if "Aaron" or "Othello" (arrogant murderer of a trophy wife) have widely used slurs against people of North African ancestry.

Not to haggle over levels of anti-Semitism (!), but you've said something really interesting that I have to respond to.

I disagree that:

"Part of the reason it's hard for Jewish audience members of The Merchant of Venice to disentangle the anti-Semitic material from the overall theme of the entanglement of love and money (both major themes of the Italian comedy) is because just such an entanglement is a central anti-Semitic trope."

To be specific, I disagree with the idea that "just such an entanglement" is actually Shakespeare's message. That's T.S. Eliot's message, surely - Eliot sees Judaism as the antithesis of the central Christian trope of transcendent love - and why Eliot is, indeed, an anti-Semite.

Shakespeare, however, is bigger than Christianity, and he subverts Christian ideals quite thoroughly in Merchant. He even subverts that "entanglement" you're talking about.

Let's look at Act V. It's a long meditation on what kind of contract can be broken, and what kind can't. Shakespeare's general point is that contracts of love are inviolate, while legal contracts must bend to the "quality of mercy." But hold on, hold on - just ponder for a moment that the central symbol of the "love bond" in Act V is Portia's ring. But Shylock, too, had a ring - stolen from him by Jessica. For me the most piercing moment in the play is when Shylock cries that he had that ring "of Leah, when I was a bachelor." It's a small point, but the kind of point that overturns utterly a simplistic, anti-Semitic reading of Shylock. He was true to Leah - he treasured her ring - while Bassanio is not, actually true to Portia (he gives Portia's ring up). And it's the theft of his love-bond that drives Shylock over the edge.

So as you can see, Shakespeare identifies Shylock with love as well as money - he is, in fact, probably the most romantic person in the play.

I'm not sure I want to claim Shakespeare had a message (as much out of my own post-modernism, as because he seemed to take too much pleasure in creating ironies and contradictions to stay "on message.") However, there's the matter of how the play is interpreted as a historical artifact, and even if Shylock is arguably the most romantic character in the play (a point with which I agree, for precisely the same reasons you state) the point is that in the popular imagination he has resonated instead with some of the most recurrent of anti-Semitic tropes of Jews and money.

Again, it's what the audience has made out of Shylock for most of the ~412 years since the play was first staged, which is far less nuanced than what is there in the text, and could be brought out in a sensitive production.

I also like the point you make that Shylock, by the time he is in court, has gone over the edge. His lust for vengeance is not a Jewish trait (though audiences seem to have long interpreted Shakes as saying such) but of having lost everything important to him: daughter (thus future progeny,) the memento of his wife's love, the security of his home and livelihood. The bond is all he has left. So there is a Job parallel as well.

Sorry to butt in the conversation years after the fact. Just to say I love the Shylock Job connection you make, where previously I’ve only seen the Antonio Job connection.

Post a Comment