Photo by Erik Jacobs for The Boston Globe click here for full size.

Starting another summer teaching mime and commedia dell'art at the Somerville-based, Open Air Circus. This will be my sixth summer with the community-based youth circus and in addition to teaching, I am learning stilt-walking (and finding it surprisingly easy.)

There's still time to register for classes! Contact Peter Jehlen at peter_jehlen@openaircircus.org

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

Running Back to the Circus

Posted by

Ian Thal

at

6:58 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: commedia dell'arte, mime, Open Air Circus, teaching

Saturday, June 12, 2010

Henry V meets John Yoo for Fun and Torture

[N.B.Thomas Garvey's account of the same event is at The Hub Review.]

"What," you might ask me, "would bring you of all people to a Federalist Society function?" What if I told you that the function was co-sponsored by Commonwealth Shakespeare Company that it was a staged-reading of Henry V followed by a panel discussion entitled "Shakespeare's Henry V And The Law And War" featuring former White House Chief of Staff, Andrew Card, and former Deputy Assistant Attorney General, John Yoo who is generally credited with authoring the memos that are now seen as laying the legal groundwork for the Bush administration's use of torture?

The Federalist Society is an association founded by conservative and libertarian lawyers and judges associated with the Reagan administration. Their rallying cry is "original intent" (or as Yoo would tellingly joke in the panel discussion, "Our original intent." A quick look at the list of participants made it very clear that the evening's agenda would likely be using Shakespeare's play to validate the Bush administration's wartime record.

Of course, when Commonwealth Shakespeare Company director Steven Maler last staged Henry V it was in 2002, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. The framing narration was set in the London tube during the Battle of Britain, when the underground doubled as a public bomb shelter for the people of London seeking refuge from German bombs and rocket attacks:

The narrator was a glamourous woman in green who tells the story of King Harry's victory in Agincourt to reassure a little boy who fled underground while still in his pajamas that Britain and its allies will ultimately emerge victorious over the Germans:

So given the time, when many Americans were still reeling from the September 11 attacks, and political consensus had not yet been rattled by the morass that emerged in Iraq, the allegory that director Steven Maler was presenting was clear: King Harry's multinational army (which is presented as including English, Scots, Welsh, and Irish) were standing in for the Allied forces who fought the Axis powers during World War II, who in turn, were standing in for the multinational North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces who were deploying against al-Qaeda and their Taliban supporters in Afghanistan. Never mind that Harry's claim on France was probably as dubious as Germany's claim on the Sudatenland, Silesia, Alsace-Lorraine, and other parts of Europe that were incorporated into Großdeutschland. That's the problem with allegories: they start to break down once one extends them too far.

It was probably the most brilliant piece of political propaganda I had seen on stage. That this is not a criticism: Henry V, like all of Shakespeare's histories, contain elements of propaganda. This was just the most effective use I had seen of those elements. Contrarily, Actors' Shakespeare Project more intimate 2008 production which had been staged after pubic dissatisfaction with the Iraq war was widespread, gave greater emphasis on the hard lives of the soldiers than on Henry's heroic status (though it was also the most effective performance of the courtship of Henry and Katherine I've seen-- but maybe that's just because Molly Schreiber rocks. Disclosure: I frequently usher for ASP.)

"How did you like the play, Mister Thal?" The text was dramatically cut to only a little more than an hour, but that was just as well as Thomas Garvey noted lawyers don't make very good actors. They were mostly adequate in the chorus but lacked the ability to present characters or hint at subtext, something most actors seem to be able to do even when reading cold. Former Lieutenant Governor Kerry Healey was actually somewhat amusing as Princess Katherine (she had played the role before.) Senior Vice President of Raytheon and former Associate Attorney General (2001-2002) seemed to be cast as King Henry largely due to his physical resemblance to George W. Bush: As we will see, the George and Henry comparisons would never end, though they seemed pretty much limited to the idea of a ne'er-do-well son of a political dynasty ascending to power despite most observers' low expectations and then starting a war. Oh yes, did I mention the dubious causae belli? Actually, none of the panelists made any of explicit comparisons, they only encouraged me to free-associate.

In his remarks, Bernard Dobski of Assumption College noted that Henry rejected Christian just war theory in his formulation of his causae belli as well as in many of his wartime actions (though he left out that he received approval from the Church to make unprovoked war) and made some non-argument that Henry was upholding the dignity of the law even as he was acknowledging the "incompleteness" of the law. Dobski forgot that in the play, the Church appears to have abandoned just war theory as well.

Michael Avery, in his role as the panel's token left-winger, suggested that Shakespeare should write a play called George II about a monarch who claims the power of the unitary executive, that no treaty or domestic law puts limitations on a president's war powers while making hypothetical claims of weapons of mass destruction, with Colin Powell in the role of the hero. David Hare already wrote that play: it's called Stuff Happens. Avery then pointedly addressed John Yoo by noting that when one wars upon the Constitution one wars upon the country. This an added extraordinary level of irony to Andrew Card's earlier fantasia of George W. Bush thinking about his Presidential Oath of Office on September 11, 2001 after he told Bush that the country was under attack:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.Republicans have problems with irony.

Yoo had apparently also never heard of David Hare and suggested a sequel entitled Obama I in which George II's successor loses all of his predecessor's gains (by contrast, Andrew Card would prove to be more charitable, applauding President Obama's intellect and ability to make decisions based on intelligence reports that, as president, he receives on a daily basis). Before I go into the details of John Yoo's arguments, let me note how disappointed I was with his performance. I had been expecting him to have a coherent legal theory, but instead he seemed to be relying the idea that we in the audience was not paying close attention, he also seemed not to have understood the play and generally had problems distinguishing between a 16th century dramatization of 15th century politics and 21st century political reality. Card had similar problems but, he's an apparatchik and not an academic.

Yoo rather anachronistically appeared to view Harry's seeking Church permission to wage war on France as George Bush's moral authority to wage war over and against any objections from the international community. Yoo seemed to miss that the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely do not make any moral claims, but rather support Henry's belligerance out of their own political interests, and furthermore: the Church they represent was the equivalent of the international community. Yoo will continue to talk of morality above the law as justification for Henry and George's decisions to flaunt both jus ad bellum and jus in bello in the interest of political expediency. He expanded on this by pointing out the inability of the international community today embodied by the United Nations to represent a universal morality when many of the nations are dictatorships. Instead of insisting that the international community be held to higher standards Yoo took the sophistic position of moral nihilism. Despite Henry's threats to the citizens of Harfleur, Yoo continues to claim Henry fights on behalf of morality:

If not, why, in a moment look to seeMoral nihilism goes beyond the realm of simple amoralism in that it makes continual reference to the language of morality, i.e. Yoo's call for a morality that is above the amoral standards of the international community while endorsing the claim that no moral standard, not even the moral standards of the United States as embodied in U.S. laws, should bind the President and even argues on behalf of specific actions that arguably have no practical purpose: like torturing children. I would be tempted to call John Yoo the "Noam Chomsky of the right" in light of Chomsky's own morally nihilistic apologetics for genocide, terrorism, and genocide denial, except that Chomsky is really little more than a self-aggrandizing cult-leader, and John Yoo is a moral nihilist with political influence.

The blind and bloody soldier with foul hand

Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters;

Your fathers taken by the silver beards,

And their most reverend heads dash'd to the walls,

Your naked infants spitted upon pikes,

Whiles the mad mothers with their howls confused

Do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry

At Herod's bloody-hunting slaughtermen.

What say you? will you yield, and this avoid,

Or, guilty in defence, be thus destroy'd?

(III.iii 33-43)

[Doug Cassel asked]"If the president deems that he's got to torture somebody, including by crushing the testicles of the person's child, there is no law that can stop him?"Of course, in the interests of the "civility" that the Federalist Society maintains for its panel discussions, the act of crushing children's testicles wasn't discussed, while the sadomasochistic techniques seen at Abu-Ghraib were only alluded to and waterboarding, whose use by the Spanish Inquisition was widely condemned by 16th century English writers (Shakespeare's contemporaries) as barbaric, was only mentioned in passing.

"No treaty," replied John Yoo.

Card and Yoo were clearly focussed on a defense on the Bush administration's wartime record. Both of them using the September 11, 2001 attacks as the causae belli for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Insisting that the threat of terrorism had changed the rules. Thus Card engaged in apologetics for the "are you with us or against us" doctrine noting that the invasion of Iraq was necessitated by Iraq not being "with us." Of course, Card was rewriting history: Iraq had already caved in to international pressure and had permitted UN arms inspectors to return, the Coalition invasion of Iraq was done before the arms inspectors could finish their job and was without regard to what they had not discovered. Speaking of writing history, they also frequently evoked the war records of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as giving legitimacy to Bush policy. Note: Lincoln and Roosevelt were demonstrably, highly effective war-time presidents who also did perceive limits on even their most controversial exercises of power while neither case can be made for Bush. Defense attorney J.W. Caney Jr., who had played Fluellen, raised the point that the measure of a society's justice system is how it treats those whom the society despises,but ultimately, neither Bush administration veteran could make the case that either the particular acts of the administration: invasion without a justifiable causae belli, the use of torture, extraordinary rendition, or the theory of the unitary executive who is above and not bound by treaties, laws, or the Constitution he is sworn to defend was actually needed in order to defend democratic societies from either foreign nation states or terrorists. All they could say was that the world had changed after 9/11 and unreflectively enlist a misreading of a truncated version of Henry V to support their thesis.

Card and Yoo were clearly focussed on a defense on the Bush administration's wartime record. Both of them using the September 11, 2001 attacks as the causae belli for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Insisting that the threat of terrorism had changed the rules. Thus Card engaged in apologetics for the "are you with us or against us" doctrine noting that the invasion of Iraq was necessitated by Iraq not being "with us." Of course, Card was rewriting history: Iraq had already caved in to international pressure and had permitted UN arms inspectors to return, the Coalition invasion of Iraq was done before the arms inspectors could finish their job and was without regard to what they had not discovered. Speaking of writing history, they also frequently evoked the war records of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as giving legitimacy to Bush policy. Note: Lincoln and Roosevelt were demonstrably, highly effective war-time presidents who also did perceive limits on even their most controversial exercises of power while neither case can be made for Bush. Defense attorney J.W. Caney Jr., who had played Fluellen, raised the point that the measure of a society's justice system is how it treats those whom the society despises,but ultimately, neither Bush administration veteran could make the case that either the particular acts of the administration: invasion without a justifiable causae belli, the use of torture, extraordinary rendition, or the theory of the unitary executive who is above and not bound by treaties, laws, or the Constitution he is sworn to defend was actually needed in order to defend democratic societies from either foreign nation states or terrorists. All they could say was that the world had changed after 9/11 and unreflectively enlist a misreading of a truncated version of Henry V to support their thesis.

Posted by

Ian Thal

at

9:41 PM

5

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: Andrew Card, commonwealth shakespeare company, federalist society, George W. Bush, Henry V, Iraq, John Yoo, Shakespeare, steven maler, torture, World War II

Launcelot Gobbo, Old Gobbo and Les Gobbi, Part 2

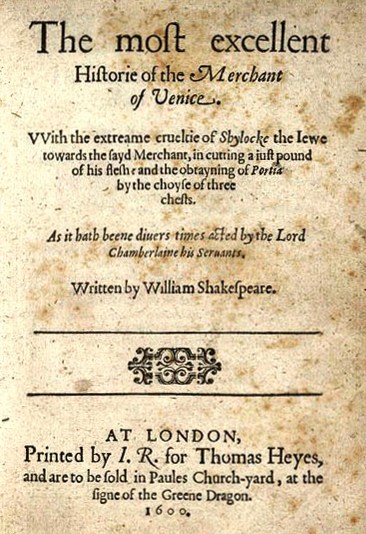

After discovering that Jacques Callot had illustrated a series of sketches of a troupe of dwarf actors and musicians known as Les Gobbi I naturally wondered "what connection might exist between this troupe and the characters of Old Gobbo and Launcelot Gobbo from The Merchant of Venice?" Though the possible connection certainly supports directors and dramaturgs to making some unconventional casting decisions, I confess that my speculation was not vigorously supported by the evidence, as Callot clearly made the illustrations long after the publication of The Merchant of Venice and I had no evidence as to how long the troupe had existed or if an earlier version of the troupe could have been known in England.

After discovering that Jacques Callot had illustrated a series of sketches of a troupe of dwarf actors and musicians known as Les Gobbi I naturally wondered "what connection might exist between this troupe and the characters of Old Gobbo and Launcelot Gobbo from The Merchant of Venice?" Though the possible connection certainly supports directors and dramaturgs to making some unconventional casting decisions, I confess that my speculation was not vigorously supported by the evidence, as Callot clearly made the illustrations long after the publication of The Merchant of Venice and I had no evidence as to how long the troupe had existed or if an earlier version of the troupe could have been known in England.

However, the Victoria and Albert Museum has in its collection a set of porcelain figures based on Callot's illustrations of Les Gobbi, and their website stated that these "grotesque dwarf entertainers" performed at the Medici court.

I checked the index of Pierre Louis Duchartre's classic work on the history of the commedia dell'arte, The Italian Comedy and found no reference to Les Gobbi, though other troupes of the era are mentioned. Of course Duchartre has some bizarre discomfort with the more vulgar elements of the commedia dell'arte, and might have been tempted to disregard a troupe who could be described as "grotesque" no matter how popular, even if, as the illustrations indicate, at least some of them were masked actors.

John Russell Brown, in his introduction to the Arden edition of The Merchant of Venice also notes that:

John Florio's Italian dictionary, A World of Words (1598), gave "Gobbo, crook-backt. Also a kind of faulkon."Though A World of Words was likely published after Shakespeare had composed and produced The Merchant of Venice there is some indication that even in England of the 1590s that "gobbo" was used as a term of derision for those with hunched or crooked backs, at least amongst those who had some passing familiarity with Italian. I know Shakespeare well enough to know that he did not shy away from vulgarity, or anything that our 21st century liberal ears would find too cruel to utter in polite society-- and certainly some of Callot's Gobbi are "crook-backt." Of course, there is also some possibility that Shakespeare and Florio were acquaintances and shared a fondness for insults.

Brown also offers the countering hypothesis that since the first quarto often renders "Gobbo" as "Iobbe" (spelling was not standardized back in 1600) that perhaps Shakespeare intended to provide an Italianized form of the Biblical Job. To me, this is doubtful, as the strongest Biblical allusion related to the Gobbi is that of Isaac and Jacob both in terms of Launcelot's tricking his blind father, as Jacob tricked his blind father, and Launcelot's prolific nature which is a somewhat comic parallel to Jacob's own fathering of the Twelve Tribes of Israel (and let us not forget the pun in the younger Gobbo's name: "Lance-a-lot.") If anything, the rendering as "Iobbe" should be taken less as a literary allusion than a hint for how the name should be pronounced on stage.

Knowing Shakespeare, and knowing that The Merchant of Venice was seen by his company and his audiences as a comedy, I'm more inclined to buy the idea that Shakespeare meant Launcelot Gobbo to be understood as "promiscuous crook-backed fellow" and not as some non-existent allusion to Job, the most tragic book in Jewish scripture.

Still, I have no evidence supporting the Callot connection, but given the utter silliness of Brown's Job hypothesis I am amazed I've not come across anyone else making a connection between Les Gobbi of Shakespeare and Callot.

Posted by

Ian Thal

at

7:53 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: commedia dell'arte, Gobbo, Jacques Callot, Merchant of Venice, Pierre Louis Duchartre, Shakespeare