After discovering that Jacques Callot had illustrated a series of sketches of a troupe of dwarf actors and musicians known as Les Gobbi I naturally wondered "what connection might exist between this troupe and the characters of Old Gobbo and Launcelot Gobbo from The Merchant of Venice?" Though the possible connection certainly supports directors and dramaturgs to making some unconventional casting decisions, I confess that my speculation was not vigorously supported by the evidence, as Callot clearly made the illustrations long after the publication of The Merchant of Venice and I had no evidence as to how long the troupe had existed or if an earlier version of the troupe could have been known in England.

After discovering that Jacques Callot had illustrated a series of sketches of a troupe of dwarf actors and musicians known as Les Gobbi I naturally wondered "what connection might exist between this troupe and the characters of Old Gobbo and Launcelot Gobbo from The Merchant of Venice?" Though the possible connection certainly supports directors and dramaturgs to making some unconventional casting decisions, I confess that my speculation was not vigorously supported by the evidence, as Callot clearly made the illustrations long after the publication of The Merchant of Venice and I had no evidence as to how long the troupe had existed or if an earlier version of the troupe could have been known in England.

However, the Victoria and Albert Museum has in its collection a set of porcelain figures based on Callot's illustrations of Les Gobbi, and their website stated that these "grotesque dwarf entertainers" performed at the Medici court.

I checked the index of Pierre Louis Duchartre's classic work on the history of the commedia dell'arte, The Italian Comedy and found no reference to Les Gobbi, though other troupes of the era are mentioned. Of course Duchartre has some bizarre discomfort with the more vulgar elements of the commedia dell'arte, and might have been tempted to disregard a troupe who could be described as "grotesque" no matter how popular, even if, as the illustrations indicate, at least some of them were masked actors.

John Russell Brown, in his introduction to the Arden edition of The Merchant of Venice also notes that:

John Florio's Italian dictionary, A World of Words (1598), gave "Gobbo, crook-backt. Also a kind of faulkon."Though A World of Words was likely published after Shakespeare had composed and produced The Merchant of Venice there is some indication that even in England of the 1590s that "gobbo" was used as a term of derision for those with hunched or crooked backs, at least amongst those who had some passing familiarity with Italian. I know Shakespeare well enough to know that he did not shy away from vulgarity, or anything that our 21st century liberal ears would find too cruel to utter in polite society-- and certainly some of Callot's Gobbi are "crook-backt." Of course, there is also some possibility that Shakespeare and Florio were acquaintances and shared a fondness for insults.

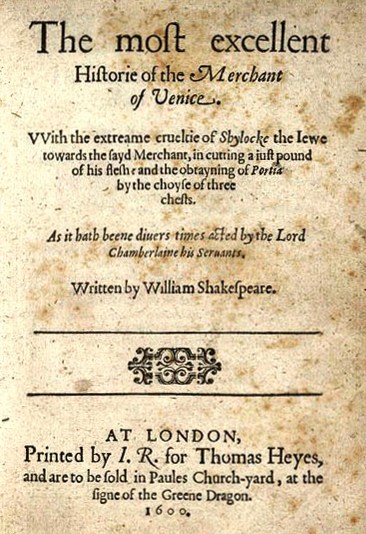

Brown also offers the countering hypothesis that since the first quarto often renders "Gobbo" as "Iobbe" (spelling was not standardized back in 1600) that perhaps Shakespeare intended to provide an Italianized form of the Biblical Job. To me, this is doubtful, as the strongest Biblical allusion related to the Gobbi is that of Isaac and Jacob both in terms of Launcelot's tricking his blind father, as Jacob tricked his blind father, and Launcelot's prolific nature which is a somewhat comic parallel to Jacob's own fathering of the Twelve Tribes of Israel (and let us not forget the pun in the younger Gobbo's name: "Lance-a-lot.") If anything, the rendering as "Iobbe" should be taken less as a literary allusion than a hint for how the name should be pronounced on stage.

Knowing Shakespeare, and knowing that The Merchant of Venice was seen by his company and his audiences as a comedy, I'm more inclined to buy the idea that Shakespeare meant Launcelot Gobbo to be understood as "promiscuous crook-backed fellow" and not as some non-existent allusion to Job, the most tragic book in Jewish scripture.

Still, I have no evidence supporting the Callot connection, but given the utter silliness of Brown's Job hypothesis I am amazed I've not come across anyone else making a connection between Les Gobbi of Shakespeare and Callot.

3 comments:

In the mid to late 1940s, my father was a student and City College of N.Y. and working at the Rockefeller Institute. Dad related this "story" to us when we were children: His Jewish boss--actually the boss of dad's supervisor, Dr. Jacobs, invited dad into his office and told him they must be related. Dr. Jacobs went on to explain that Gobbo and Jacobi come from the same root. We never learned whether this was true, but your blog post has added to my curiosity. Dad's parents came from Veneto, the region in Northern Italy that also includes Venice. Dad told us about Launcelot Gobbo when we were children, part of his mission to help us better understand our roots.

There’s a lot to be said about the connection of Job to The Merchant of Venice. Antonio’s loss of ALL the ships is just too convenient a plot point to be taken realistically, and has a much better ring as a literary allusion. So is the three casket plotline. I don’t think old Shakes is averse to little bits of allusions and double speak sprinkled into his plays, and maybe in later editions the commedia allusion won out.

Thanks for commenting! It gave me a chance to review something I wrote many years ago on a blog that has been dormant for a very long time. This was part of some of the preliminary research I engaged in before I started writing what would become a sequel to The Merchant of Venice.

The core story of MOV is adapted from a story that appears in the short story anthology Il Pecorone by the Florentine writer Giovanni Fiorentino. The story features the Florentine merchant Ansaldo, his god-son Gianetto, an unnamed wealthy widow that Giantto wishes to marry, and an unnamed Jewish moneylender. Shakespeare changes the names and location. So if Shakespeare intended any reference to Job, it was incidental, but as I noted, since Shakespeare already recounts one of the stories of Jacob and Laban in Act I, the other allusions to Jacob are fairly obvious. It's simply a matter that I don't buy John Russell Brown's suggestion that there is a connection between Gobbo (either old or young) and Job.

The three-caskets plot is generally believed to be taken from the Latin anthology Gesta Romanorum which was available in English translation by 1595. I suspect that Shakespeare felt that Portia would garner more sympathy from the audience as a rich orphan upon whom the test was imposed by a deceased father, than a rich widow who was imposing the test herself.

Post a Comment