Tuesday, June 21st, 2011, I attended the eleventh annual staged readingand symposium on Shakespeare and the Law jointly presented by the Boston Chapter of the Federalist Society and the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company. I did not know what to expect : last year's reading and discussion of Henry V had been little more than alove-fest for John Yoo and his legal arguments on behalf of George W. Bush's more controversial war-time decisions that inadvertently exposed Professor Yoo's intellectual poverty. However, since the play under consideration was The Merchant of Venice, a play that has been in my thoughts in recent years, I felt the need to attend. By coincidence, the Cutler Majestic Theatre, which hosted the event was the very same room in which I had seen Darko Tresnjak's Theatre for a New Audience production of Merchant of Venice

As with the previous year's presentation, the affair was a highly truncated reading by non-actors (in this case a cast made entirely of judges) that clocked in at about an hour, followed by a panel discussion on the legal themes. It was a pleasant surprise that this year featured as more sober, less partisan discussion than last.

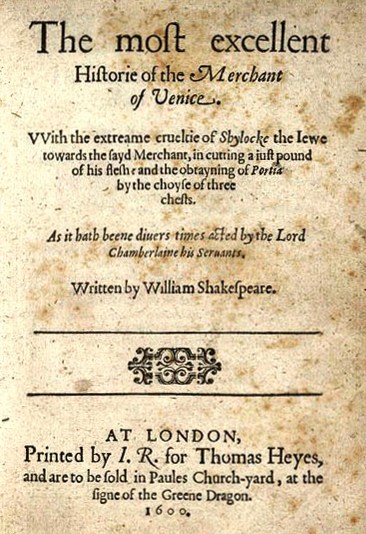

Daniel J. Kelly, Chairman for the Boston Chapter of the Federalist Society, in his role as moderator, established the themes under consideration as "contract, equity, justice, and judging" as such, the scenes that were featured in the reading were those that focussed on the three types of contracts that appear in the play and their related trials: infamous bond of the pound of flesh between Shylock and Antonio and Act IV's trial scene, the will that stipulates the "obtayning of Portia by the choyƒe of three cheƒts" and the oaths regarding the wedding rings and comic early morning trial in Belmont. Helen M. Whall, professor of English at College of the Holy Cross, opened the after-play discussion, offering some of the scholarly insights that were lacking in last year's far more partisan presentation.

I am unable to account for all of the speakers and their insights but I will sketch out some notable comments as well as some general points of consensus.

Whall noted that prior to the incorporation of the first professional theatre company in England in 1576, the primary theatrical experience had been that of morality plays (a genre satirized in Launcelot Gobbo's monologue cut in this version) and thus Shakespeare's audience were accustomed to having such concepts of law, mercy, and justice allegorically dramatized on the stage. Most importantly, Whall underlined that from the Christian perspective of the 1590s, the forced conversion of Shylock from Judaism to Christianity that so upsets the sensibilities of those of us who live in countries that guarantee religious liberty would be seen as a favor (indeed, an act of "mercy.") As this theological perspective is central to my thoughts regarding the play, I will return to it later.

Judge Andrew Grainger of the Massachusetts Appeals Court, who had played the role of Shylock in the reading, was very quick to point out that despite the literary worth of The Merchant of Venice that not only was there a problem of overlaying our 21st century legal sensibilities upon a 16th century play that there were also limitations to how a literary and dramatic presentation can be seen as representing the operations of the law. This was a theme that several of the judges brought up (in fact, Gabrielle Wolohojia, also of the Appeals Court, who played Portia, expressed a strong distaste for Portia's legal practice): Portia's courtroom behavior would at the very least allow Shylock the right of appeal in a modern, western court. Besides impersonating a judge and entering the court under false credentials (not mentioned by the panelists) she has a number of conflicts of interest: the defaulted loan was taken on her husband's behalf, combined with her money being offered in settlement presents her with both a personal and financial stake in the outcome of the trial. Portia also, on a whim, changes roles from judge, to defense attorney, to prosecutor and back, while simultaneously turning what is essentially a civil trial of Antonio into a criminal trial of Shylock.

Daniel Kelly would point out that Portia reads all sorts of conditions into the bond that were not already in the bond in such a way that undercuts the rule of law (indeed, it is precisely by her reading in of conditions that she flips the trial of Antonio into a trial of Shylock.) Of course, several of the Judges present pointed out that whether Shylock was willing to accept a settlement or not, the conditions of his bond (the forfeit of the pound of flesh) were legally absurd and "void as against public policy"-- i.e. the contract would be dismissed because it required an illegal act for its fulfillment. Relying on Jean Favier's history, Gold & Spices: The Rice of Commerce In the Middle Ages it appears that courts did have the power to dismiss bonds of usury if it was determined that the contract placed too onerous a burden upon the debtor (such as something that would be otherwise illegal)-- in which case, the usurer might be subject to a small fine (but never one so harsh to keep the usurer from returning to the business) so despite even Antonio's claims that

The duke cannot deny the course of law:--the "course of law" did then, as it does now, provide an escape from the bond. It is precisely this principle of "void as against public policy" that allowed my parents to purchase the house in which I grew up despite a deed specifically barring "Jews and Negroes" from residing within; such restrictive covenants had been rendered unenforceable by Shelley v. Kraemmer (1948) even if the deeds continue to exist.

For the commodity that strangers have

With us in Venice, if it be denied,

Will much impeach the justice of the state,

Since that the trade and profit of the city

Consisteth of all nations…(Act III, Scene 3, 26-31)

The point being that while Portia demands Shylock be merciful, rather than doing to merciful thing which would be voiding the bond (and perhaps returning Shylock's stolen property), she threatens Shylock with death.

We do see that Portia is quite willing to manipulate the law to further her own agenda not just in the Venetian court (where she is called in a judge, not as an advocate) but in regard to the trial of the three caskets: she is willing to play by the rules, but she also actively schemes to ensure that the suitor that pleases her choose rightly and the suitor that does not choose wrongly:

Therefore, for fear of the worst, I pray thee, set aOr in this song to Bassanio:

deep glass of rhenish wine on the contrary casket,

for if the devil be within and that temptation

without, I know he will choose it. I will do any

thing, Nerissa, ere I'll be married to a sponge.(Act I, Scene 2, 91-95)

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart, or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?(Act III, Scene 2, 63-65) [Emphases mine own; they all rhyme with "lead" as in casket.]

This of course, does beg the question as to what causes Portia to threaten Shylock's life, humiliate him, and force his conversion when there was a legal means of voiding the cruelest provisions of the bond and compelling a settlement by which Shylock would be paid the capital, as well as the secondary question as to what made this a pleasing resolution to an Elizabethan audience. First of all, we must follow Grainger's warning not to impose our 21st century sensibilities upon this 16th century play. Whall was correct to note that the forced conversion that is so offensive to 21st century American sensibilities, was, to the at least nominally Christian audience of the 1590s, an act of mercy. Not in the sense that he only had to change his house of worship to avoid the death penalty, but (as I have argued elsewhere) Christian theological positions with regards to Judaism.

As I have noted in my essayregarding the Theatre for a New Audience production, Darko Tresnjak did an excellent job of bringing The Merchant of Venice into the 21st century, and used the play to show how antisemitism can continue to thrive in our age, but in doing so, he lost sight of the anti-Judaism of the 1590s and how that informs both the language and ideology of the play and failed to explain why Jew-hatred is so atavistic: it is rooted not in simple doctrinal misunderstanding, but in folklore and in Christianity itself.

Until Shylock insists on collecting his pound of flesh, he commits no act of villainy. All crimes are committed by Antonio (who is proud to own up to kicking and spitting upon Shylock) and his gang of Bassanio, Lorenzo, Salerio, and Solanio who rob Shylock's house after Antonio lures him away from home. Why does Shylock demand a pound of flesh? When asked, Shylock can only answer:

You'll ask me why I rather choose to haveThe answer is that it is simply what Jews do in European literature. The tale of the Merchant of Florence, Bindo Scali, from Ser Giovani Fiorentino's Il Pecorone (Composed in 1378 though published in 1554), also has a Jewish money lender who demands a pound of flesh, as does the titular Jew of The Ballad of Gernutus. Indeed the story appears throughout European folklore. While storyteller, theatre artist, and folklorist, Diane Edgecomb has informed me that she has come across older versions of this story in Kurdish folklore, in which the money lender is a Christian, it should be noted that the "pound of flesh" dovetails with the blood libel. In short, while it takes an injustice to motivate Shylock towards revenge, the particularly grotesque nature of his vengeance conforms to European prejudices of how Jews behave.

a weight of carrion flesh, than to receive

three thousand ducats: I'll not answer that!

But say it is my humour, --is it answer'd?Act IV, Scene 1, 40-43)

The sentence is also grotesque by Venetian standards. While other Catholic nations allowed the the Universal Inquisition free rein, The Republic of Venice granted Marranos, Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity and their descendants who continued to practice some form of Judaism in secret, the right to revert to Judaism without persecution by the Inquisition (see either Cecil Roth's 1932 classic A History of the Marranos or Jane S. Gerber's 1993 The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience.) In other parts of the Catholic world, both in Europe and New World colonies, these Marranos were subject to imprisonment, torture, and execution. Forced conversions may have been the norm elsewhere in Europe; but not in the Serene Republic.

Leaving aside Portia's afore mentioned ethical lapses, it's a theological imperative that results in the sentence against Shylock. The law that is operative in Shakespeare's courtroom, isn't the law of the Republic of Venice, but scripture and its Christian interpretation. Furthermore, when Shylock defends his lending of money at interest as a profession, he does not reference a major trade empire's needs to acquire liquid assets with which to invest in a new venture or deal with an unforeseen setback (something a merchant prince like Antonio would understand) but with reference to scripture, using the story of Jacob tending the flocks of Laban to justify the practice. The question is not economic necessity but the status of Jewish scripture in Christian Europe.

(As a side note: given that loaning at interest a normal business practice in Europe at the time, especially in northern Italy, the fact that Antonio would be seeking a loan from the despised Shylock implies either a desire to set Shylock up or that Antonio has bad credit with all the Christian money lenders.)

As I have argued previously (most recently in my notes on Tresnjak's production) the issue of mercy in Act IV is a theological proposition of the superiority of Christianity over Judaisim: Shylock, the Jew, may have the Law, but he only receives God's mercy by becoming Christian; conversely, the Venetian and Belmontean characters all commit sins: they are accessories to theft, they break oaths, impersonate court officials, yet are recipients of God's mercy on account of being Christians.

This has long been, in the eyes of Christian theologians, the dividing line between Judaism and Christianity: Judaism is presented as a religion of strict laws while Christianity is the religion of mercy (again note Whall's point that Shakespeare's audience was familiar with the allegorical morality plays as well as the sermons of any number of Christian sects, both Catholic and Protestant and as such Mercy and Law could be real characters to them) so not only have we Shylock defending his profession through reference to scripture, but in the courtroom scene he proclaims:

My deeds upon my head! I crave the law,Note that this adherence to "the law" is in the same breath as a line that echoes the "blood curse" from Matthew, 27: 24-25 "His blood be on us, and our children" -- in short, the very passage that Christians had used to place the blame of Jesus' crucifixion upon Jews of subsequent generations.

The penalty and forfeit of my bond.(Act IV, Scene 1, 202-203)

"Law" in The Merchant of Venice is not merely civil law or criminal statutes, but also scripture. Consequently, this dichotomy between mercy and the law is also one of Christianity and Judaism as imagined by Christianity. Christianity has long had the ambivalent position of both insisting that Jewish scripture, the Tanakh was the proof that the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth had fulfilled messianic prophecy, and thus validated the new religion over the old, while also having to contend with the continuing existence of Judaism in the Christian era. The question became one of "if Jews know the prophecies, how could they deny Jesus?"

This question came to a head for Christian theologians during the late middle ages, when in 1230s, the Inquisition, whose mission had up until then to regulate the beliefs of Catholics, intervened in a theological dispute between rabbis over Moses Maimonides' Guide of the Perplexed. While in 1240 Pope Gregory ordered the mendicant orders of the Dominicans and the Franciscans to seize and burn any copies of the Talmud and other Jewish texts a containing doctrinal error. Rabbis were summoned by the Inquisition. This continued under subsequent Popes. The belief was held that the Talmud and other interpretive commentaries had not only strengthened Jewish resolve to reject Christianity, but that exposure to Jewish texts would result in Christian heresy. In short, the Inquisition, with papal backing, decided that it had the authority to determine orthodox versus heterodox Judaism using the weapons of imprisonment, torture, and execution.[Note: I am greatly indebted to Jeremy Cohen's The Friars and The Jews: The Evolution of Medieval Anti-Judaism (1982) regarding the role of the Dominican and Franciscan orders in the persecution of Jews and the formulation of an anti-Judaic ideology.]

By the time of the Barcelona Disputation of 1263, Dominican Friar Pablo Christiani (a Jewish convert once named Saul) had gone so far as to argue that the Talmud reveals that Jewish sages were not merely misguided but that they believed Jesus to be both God and Messiah while also refusing to reject Judaism and adopt Christian rites and beliefs out of sheer wickedness. Rabbi Nachmanides' (who had been forced to defend Judaism in a court whose rules were determined by the Inquisition) response ultimately was that Christiani was presenting a heretical interpretation of the Talmud as well as misrepresenting the canonical status of Talmudic texts. The dispute was largely an aporeia, in part because Nachmanides was barred from presenting certain counter arguments at the very outset of the disputation. Both sides claimed victory, but ultimately the disputation failed to convert Spanish Jewry.

So by the time of Franciscan Hebraist Nicholas of Lyra (c. 1270-1349) composed his Quodlibetum de adventu Christi, he had actually argued that the sole reason the Hebrew text of the Tanakh provides enough ambiguity for Jews to deny that it validates and foretells Jesus' ministry, and his status as both God and Messiah, was that rabbis had deliberately altered the text to deny the Christian truth:

[The Jews] here pervert the true text and deny the truth just as they deny the divinity of Christ. This might best be done from ancient Bibles, which were not corrupted in this and other passages in which there is mention of the divinity of Christ, if they [these Bibles] can be had. In this way our predecessors used to argue against them [the Jews] over this and similar passages. Yet although I myself have not seen any Bible of the Jews which has not been corrupted. I have faithfully heard from those worthy by reason of their lives, consciences, and knowledge, who swear on oath that they have seen it thus in ancient Bibles[Translation found in the aforementioned work by Jeremy Cohen.]

In short, after reading the Tanakh in Hebrew, Nicholas argued that since it did not actually state what his Church wanted it to say that the authentic Hebrew scripture had been suppressed, and that all extant copies (excepting those that he knew of through rumor) had been deliberately altered.

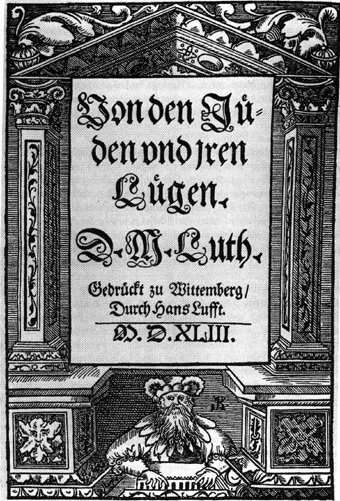

Despite England having recently become a Protestant country, these medieval Catholic views regarding Jews continued to be influential (Nicholas of Lyra's work was very influential on Martin Luther's 1543 polemic On The Jews and Their Lies) indeed it offers historical context to Antonio's response to Shylock's interpretation of the story of Shylock and Laban:

Despite England having recently become a Protestant country, these medieval Catholic views regarding Jews continued to be influential (Nicholas of Lyra's work was very influential on Martin Luther's 1543 polemic On The Jews and Their Lies) indeed it offers historical context to Antonio's response to Shylock's interpretation of the story of Shylock and Laban:Mark you this Bassanio,I have more than once noted the usage of diabolic rhetoric regarding both Shylock and Jews in general throughout The Merchant of Venice but what is notable here and perhaps chaffing to the 21st century audience is that to Shakespeare's English audiences, the Bible is not a shared text common to both Christian and Jew, but a source of division: at once both holy word in the mouths of Christians and diabolic law in the mouths of Jews and simultaneously affirming both the Christian notion that that same law is superceded by Christianity.

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,--

An evil soul producing holy witness

Is like a villain with a smiling cheek,

A goodly apple rotten at the heart.

O what a goodly outside falsehood hath!(Act I, Scene 3, 92-97)

So while I am inclined to view Shakespeare, the author, as a humanist, sensitive to the irony and ambiguity of human experience, the courtroom shenanigans of Portia, like the folkloric and literary sources he relies upon, effectively provide a theological trump to his humanism.

7 comments:

Andrew Grainger, as a judge in life and as Shylock on stage, warns against laying present legal sensibilities on a sixteenth century play. Well, it seems to me that all sorts of things are being read into the “Merchant of Venice” in your dissertation, all sorts of mistaken sensibilities, resulting in a wholly fallacious exegesis.

A lot hangs on your interpretation of mercy or ‘favour’, the mercy implied by conversion.

Forced conversion was not invariably seen as an ‘act of mercy.’ The practice was denounced as early as the seventh century by Gregory the Great. In “Constitutio Pro Judeis” Pope Innocent III, the greatest of the medieval pontiffs, wrote that “For we make the law that no Christian compel them, unwilling or refusing, by violence to come to baptism.” This was followed by a bull of 1201 that specifically denounced forced conversion. I’m not saying it did not happen; it did, most notably in the Spanish kingdoms. But the ambiguity, both in legal and moral terms, was still there.

But set this all to one side. I just think Shakespeare should be read as Shakespeare, that people as people are not so different now than they were in the 1590s; that a contemporary audience would have no direct knowledge of Jewish people, or late medieval theology. They may very well have had hostile preconceptions because of traditional Christian teachings, even if only through the stock figures used in mystery plays, but they were as capable of being swayed by simple emotion as any modern audience.

I do not believe that they would necessarily see Shylock’s conversion, accompanied by so much gratuitous humiliation, as a ‘favour,’ especially as a great many in any Elizabethan audience would have been secret Catholics, themselves obliged to observe outward Protestant forms of belief. Above all, Shylock is not a pantomime villain, much as you attempt to depict him in such terms, but a fully rounded human being. He is filled with thoughts of vengeance, yes, but he has reason to feel vengeful.

This is a play; it’s not history; it’s entertainment; it’s not a comment on the legal practices of England or Venice in the sixteenth century, it’s a fiction, a dramatic suspension of disbelief. It’s utterly wrong to assume that the plays are in any way biographical, as opposed to unique and individual works of art, penned by a man of genius and of sweeping imagination. I no more see Shakespeare as anti-Judaic on the basis of the “Merchant of Venice” than I see him as an atheist on the evidence of the “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” speech from “Macbeth.”

Portia is a character in a play; I really do have to stress the obvious here. Shakespeare uses all sorts of dramatic license, all sorts of devices, to engage his audience and build up tension and human interest. To try to draw a parallel between her courtroom antics and legal mores of the day is absurd, a bit like looking at British legal practices through modern fictional characters like Judge John Deed or Rumpole of the Bailey. I feel sure there must be an American parallel in some courtroom drama or other. I seem to remember watching a TV show set in Los Angeles, I think, one starring Jimmy Smits of “NYPD Blue”, when I was in my early teens. Was that an accurate insight into your legal practices?

I do not accept your theological trump, based, it seems to me, on a tendentious reading. But you have made up your mind, and in your mind the “Merchant of Venice” carries a burden that I will never recognise. I would just ask you to remember that the quality of mercy is not strained…just as certain judgements are not valid, including the judgements of the lawyers at your symposium. :-)

Ian, I'll post this also on Blog Catalogue.

Anastsia,

Funny that part of your argument hinges on claiming that Shylock is "a fully rounded human being" while "Portia is a character in a play." Neither statement is an argument as Shylock is also "a character in a play" and Portia is a "fully rounded" one at that. If Shylock seems "fully-rounded" it is because of Shakespeare's theatrical humanism. As I have stated before: the theological underpinnings, which give the structure and narrative thrust to both the play and the source material, trump Shakespeare's humanism.

But neither statement speaks to my argument:: my primary aim is not "correctly" interpreting the characters (that's a job for actors and I'm wearing my essayist hat today), but what the structure of the play, that is, its actions and underlying logic, say about its milieu and what its milieu says about the play's structure.

The focus on the symposium was picked by the Federalist Society (whose membership is primarily comprised of attorneys and judges) and so they were concerned with how the law was treated in the play. The guest panalist, Helen Whall, an English professor, was interested in how the legal themes could be understood as a system of metaphors. I am merely reflecting upon the discussion they were having. I have no problem acknowledging that the courtroom scene of Act IV bears no relation to an actual courtroom: I even cited several such discrepancies (though most of these discrepancies are shared with courtroom scenes of The Ballad of Gernutus and Il Pecorone.) The point is not to indict Shakespeare, but to inquire what it is about the age that demanded such a courtroom resolution?

While you are correct to cite Innocent III's disapproval of forced conversion of Jews, one must contend with the fact that the practice continued both during his life-time and afterwards. The Pontiff, might be, on a theoretical level, the absolute authority within the Church, but in historical reality, clergy have often acted autonomously. Especially when one considers the rise of the mendicant orders in the late middle ages. These friars were often at the forefront of advocating violence as a means of conversion. However compelled (and thus insincerely) these conversions were made, it was often up to local authorities as to whether these forced converts would be allowed to revert once the violence had died down-- and in most instances, reversion was not allowed. The Venetian Republic, unlike most Catholic Countries, long granted the privilege of reversion. The Netherlands, a Protestant nation, also granted such privileges (after all: why should they respect a forced conversion to Catholicism?) England only granted such rights of reversion during the Protectorate (formalizing them during the Restoration.) The point being that while forced conversion was frowned upon, the forced convert was only sometimes granted the right to reversion.

As to the 1590s London audience knowledge of Jews and theology:

The theology of the late medieval period informed the sermons, religious literature, and morality plays that members of all social classes would have encountered in that period. If one examines the anti-Catholic polemics of English Protestants or the anti-Protestant polemics of English Catholics (oft writing in exile) a common theme is to compare the other Church to the Jews. The point is that even in an England that had been bereft of Jews (outside of a handful of Marranos) since 1290, blasphemous and blood thirsty Jews were a subject of sermons, folklore, popular entertainment such as the aforementioned The Ballad of Gernutus) but also Kitt Marlowe's The Jew of Malta. The notion that secret-Catholics in Shakespeare's audience were more likely to have identified with Shylock, rather than with Antonio is not merely ludicrous but ahistorical, since it attributes liberal, tolerant sympathies to an age prior to an intolerant illiberal age (at least where Jews were concerned.)

None of this has dampened my enthusiasm for the Bard as I see, at minimum, 4-5 Shakespeare productions a year and I am most of the way through the canon. But we also have to face that The Merchant of Venicetestifies to some rather ugly aspects of British (and indeed, European) culture that stretched back centuries as we can see both in the 1594 trial and execution of Doctor Rodrigo López as well as with the recent excavation in Norwich. But with the rise in anti-Semitic violence and harassment of Jewish institutions and Jewish owned businesses in the United Kingdom and other European nations, we have to ask, how much of that is still salient?

Ian, I now think of you and I as the proverbial irresistible force and immovable object! I can certainly admire how you express yourself, and the quality of your intellect, even if I do not fully agree with your arguments.

Oh, so far as contemporary anti-Semitism is concerned you might be interested in reading Retreat from Reason, a book which I have just reviewed on my blog, which touches, albeit briefly, on this subject. It’s not as you might think. And on that cryptic note I take my leave. :-)

Okay, Ian, we promised you some sparring over this, so here goes.

First, the Federalists (according to your account) point out that it is a mistake to view the jurisprudence dramatized in The Merchant of Venice through a modern legal lens - true enough; but then they seemingly immediately begin to do precisely that. Whatever, I suppose. But for the record - Bellario/Portia is never presented as either a lawyer nor a judge, nor does she/he ever operate as either. "Bellario" is described as "a doctor of the laws," - i.e., a scholar, and his role in the courtroom is clearly an advisory one - he's a consultant to the doge, who was the ultimate judge of all that transpired in the Venice of Shakespeare's day. And he serves in that role throughout the courtroom scene of Merchant of Venice; Portia never usurps his authority. Nor does she ever operate as a prosecutor, for no actual trial ever commences during the play; Shylock is apprehended just as he is about to murder a citizen of Venice, with the officers of the court as eyewitnesses, and the doge clearly has the discretion to execute him then and there; indeed, a trial held before the doge himself to ascertain the truth of what he had just seen with his own eyes would be ridiculous on its face. (Just btw, there's no "civil trial of Antonio," either.)

There is, of course, a viable argument that Portia enters the courtroom already armed with the legal quibble that will save Antonio's life, i.e., that an obscure law on the books forbids the shedding of Christian blood, as well as the "contriving against the life" of a citizen by an "alien" (which Shylock was). To this argument there are (at least) two answers: the first is that without dramatic revelations, no play can exist. The second, deeper argument is that Portia spends much of her time in court trying to persuade Shylock to be merciful, and so save himself from a legal system he doesn't fully understand. Indeed, she never mounts any kind of counter-argument to Shylock's claims; instead she all but begs for him to relent - because she knows he's heading toward self-destruction. Your contention that she could simply void the bond with her knowledge of the law holds no real power, I'm afraid - because in simply revealing the letter of said law, she will nevertheless force Shylock's punishment. Her only option is to persuade him to drop his bloodthirsty claims of his own accord. Which he manifestly fails to do.

Once she has revealed Shylock's peril, it also must be pointed out that Portia generally sues for mercy for him, too. And the doge, at least at first, responds appropriately (he grants Shylock his life, and reduces the forfeiture of half his goods to "a fine"). I understand (and sympathize with) the horror many people feel regarding the spiritual death that Antonio then demands of his antagonist - but I sometimes think that people forget it is Antonio, not Portia, who proposes Shylock's forced conversion. Alas, the Duke backs it up with the threat of death - one of the most horrifying moments in all of Shakespeare; still, as you say yourself, forced conversions were hardly unknown in Elizabethan days, and were hardly considered the harshest punishment around.

And I also wish people would admit that the playwright himself seems to back away from this moment, even as he throws red meat to the anti-Semitic crowd. Suddenly Shylock falls all but silent - and so does Portia, which is quite strange given that in the kind of anti-Semitic folk-tales you mention, this should be the heroine's moment of triumph. It would seem Shakespeare understands that for once he has gone too far in giving the audience what it wants. And in his silence at this crucial juncture, I think you can see the beginnings of what I've called the "anti-anti-Semitism" that The Merchant of Venice eventually engendered.

Hi Tom, sorry about the lateness in this response, but a number of unforeseen circumstances delayed me somewhat.

First of all, let me point out the matters on which I agree: The Federalist Society panelists had trouble fitting the trial scene into the schema of the courtroom simply because as a work of drama (or more accurately, comedy) it wasn't meant to represent any probable trial. This is precisely why I make the point that the trial scene has to be viewed in light of both its folkloric and literary sources as well as the theological world view with which any nominal English Christian would have been familiar.

Let's face it: the trial scene makes no sense, not only in our modern Anglo-British common law traditions, but even under Venetian law of that era. It's a comedy-- just one that's hard to find amusing post-1945.

And while I agree with you that there is something in the play that allows an anti-anti-Semitic reading to take hold, I feel that any attempt to read The Merchant of Venice as a work of anti-anti-Semitism does interpretive violence, simply because most such readings are only possible by ignoring much of the anti-Semitic content. As you noted in another essay of yours (forgive me for forgetting which play you were discussing) Shakespeare's work contains the anti-thesis of every thesis he posits-- but this is not necessarily out of any political agenda but simply because the Bard was a genius who, I surmise, needed to contain ironies within ironies just to keep himself excited by the work. There is nothing in the text of the play that indicates to me that his portrayal of Shylock, Jessica, and Tubal was informed by anything but the literary, folkloric, and theological portrayals of Jews-- consequently, a truly anti-anti-Semitic reading would have to unapologetically lay bare the anti-Semitic content, but none of the productions I've seen thus far have been brave enough doing that-- (although, in an era where so many anti-Semites refuse to acknowledge that they're anti-Semites, why should that be surprising?) Such a production would be "edgier" than anything I have ever seen on Boston stages.

That said, I have to disagree with you about Portia as an advocate of mercy. I can't help but see that once Portia has disguised herself as a Doctor of law, she has aligned herself (fraudulently) not just with professional power, but with political and ecclesiastical power: she represents Christianity, the religion of mercy: also the religion with the swords, guns, and auto-da-fés against Judaism: the religion of harsh law; but also the religion of a man who gets spit upon and assaulted in public while trying to make a living. Mercy turns out to just be whatever those with the power say it is. The political and ecclesiastical power does not just say that mercy is threatening Shylock with death if he does not convert but that mercy would be Shylock forgiving the debts of Antonio, who is only unrepentant about his past assaults on Shylock's body, but party to the group who robbed his house and pursued the conversion of his daughter (indeed, Jessica's willing conversion to the religion of her father's oppressors is probably more offensive to a Jewish audience than Shylock's treatment) so Portia's mercy is aligned to criminal power as well.

I think the answer to why Shylock suddenly decides to demand a pound of flesh rather then money for no apparent reason is simple. It is establishing his credentials as a villain, so everyone can feel unambiguously good when he is defeated. I've noticed lots of authors start out with an ambiguous nuanced situation, then at the last minute realize that they forgot to have the bad guy do anything really bad, and throw some random act of evil in. They did this with Prince Humperdinck in "A Princess Bride".

As far as why Shylock doesn't offer any number of arguments that would be much better then the ones he offered...that's also quite common. If you are ever home sick and see a Soap Opera, you notice all the characters offer dumb arguments when much better ones are available. Shylock is to some extent a straw man, arguing for the lending system, but doing it badly.

Then tendency to enshrine Shakespeare as a Theater God sometimes prevent us from noticing the occasional moments of sloppy writing every writer falls victim to occasionally.

It also should be remembered that is is very possible that you and the panelists know more about the legal system of 16th century Venice the Shakespeare did. Information didn't travel as easily back then as it does now, and I've never heard anyone claim that Shakespeare was particularly well traveled. That aspects of the play weren't accurate according to the rules of the Venician legal system was probably something that Shakespeare neither knew nor would have cared about.

Post a Comment